The phases of the male sexual response have distinctive physiologic characteristics (Lue T et al. 2004a) that include the erectile process, which is a continuing series of neurovascular events occurring within a normal hormonal milieu (primarily, an appropriate level of serum testosterone) and with an intact psychological setup.

Translation? An erection does not occur on demand at a snap of the fingers. Several systems in the body and the mind team up to produce an erection. The anatomy of the penis is the foundation, but erection has certain other prerequisites: an intact neurovascular system, absence of medical or psychogenic disturbance, confidence, intimacy, receptivity, excitement, and physical attraction. Physical and psychological stimulation are also required. If any of the involved mechanisms fail, an erection can become difficult or impossible to achieve or to maintain, resulting in erectile dysfunction (ED).

The normal human male response to sexual opportunity, as originally described by Masters and Johnson (1970), comprises five phases: desire, excitement, plateau, orgasm, and refraction, as follows:

There are three different types of erections. A psychogenic erection is initiated by imaginative, visual, olfactory, tactile, or auditory stimulation. A reflexogenic erection, on the other hand, is produced by direct stimulation of the genitalia; this is also the type of erection that may reflexively occur in paraplegics (even though the injury, disease, or malformation of their spinal cord means that they aren’t necessarily aware of, or feeling, any stimulation or erection). The third type, nocturnal erection, develops repeatedly during periods of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, usually in the early morning period before awakening.

Nocturnal erection is something of a misnomer, as REM-related erections may also occur in a male sleeping for an extended time during the day. Erections during sleep serve as a natural physiological means to keep the cavernous tissues of the corpora well oxygenated. They occur from two to five times per night and last about 20 minutes each, usually decreasing with age in number, duration, and intensity.

Psychogenic erections differ neurologically from reflexogenic and nocturnal ones in their initiation and maintenance, but their final neurologic pathway is the same, and the vascular events in the penis are mostly similar.

Not exactly. The brain, however, is undoubtedly the most important human sex organ. In the male, the brain not only receives and processes erotic stimuli— touch, sight, sound, smell, taste, and thought—but also coordinates the steps essential for erectile development by sending messages (neural impulses) back through the nervous system to the penis.

I like to think of it this way: when a man is awake, alert, and not receiving any sexual stimulation, his brain sends constant signals to the penis not to get erect. If, for some reason, the brain stops sending these inhibitory signals, or the signals are not relayed properly by the spinal cord or other nerves, an unsolicited erection will probably occur. So, the brain is the main controller that facilitates or inhibits an erection’s development.

Studies taking spectroscopic MRIs during sexual excitement and erection have shown that the brain contains multiple central sex centers. The most prominent of these are located in the paraventricular medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus and the medial preoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus. The sex centers receive, integrate, and process erotic stimuli from the body and the sensory organs. The balance between pro-erectile and anti-erectile stimuli in the brain sex centers determines the message or instruction that is sent back to the body via neurotransmitters.

The type and amount of erotic stimulation necessary to summon an erection varies from man to man, and also with age.

Adolescent and young adult males usually have no problems obtaining erections, which may occur with (or without) minimal sexual stimulation. A healthy 18-year-old, for example, can get an erection simply by fantasy or other noncontact sexual stimuli. Young men can have two or three full sexual encounters, from erection to orgasm, in a short time with little or no foreplay required. Although progressive changes in a man’s sexual response usually occur by age 30, he can still easily develop an erection during kissing or foreplay. However, after age 50, he will usually need more direct sexual stimulation to achieve a firm erection.

This gradual slowing in sexual response as the man becomes more mature and sentimental has its rewards. More often than not, the love play and the sexual relationship become more meaningful and more pleasant. In older age, a healthy man is usually able to maintain good erections, but tends to require more time during foreplay to achieve one. (Note, though, that spontaneous erections occur during sleep at any age.)

I should emphasize that for any man, regardless of age, to have an erection, he generally needs an anxiety-free, relaxed atmosphere—this means no performance demands.

Numerous sensory receptors in the glans penis, penile skin, urethra, and corpora cavernosa—but not the corpus spongiosum—unite to form the dorsal nerve of the penis, which joins the pudendal nerve in the pelvis and perineum (the area between the base of the penis and the anus). Through the pudendal nerve, penile sensations are conveyed to an erectile center called Onuf’s nucleus in the sacral spinal cord. This erectile center, in turn, transmits the neural information up to the brain’s central sex centers, which are also receiving sexual/erotic stimulation from the sensory organs and the rest of the body. As previously noted, the balance between pro-erectile and anti-erectile stimuli in the brain’s sex centers determines whether or not an erection will result.

When a healthy man is aroused by erotic stimuli and the pro-erectile stimuli are sufficient for his brain’s sex centers to initiate the development of an erection, the sex centers release the neurotransmitters dopamine and oxytocin. These overcome the anti-erectile effect of the neurotransmitters noradrenaline and serotonin, thereby inhibiting the sympathetic nervous system’s usual vasoconstrictive action on the penile arteries (Lue T et al. 2004a). Dopamine and oxytocin further activate Onuf’s nucleus, the sacral spinal cord’s erectile center.

From there, parasympathetic nerves convey the neural impulses down to the penis via the cavernous nerves, causing the release of additional chemicals that are actively involved in producing an erection through penile vasodilation. Additional parasympathetic stimulation down through the pudendal nerve causes the ischiocavernous muscles surrounding the corpora cavernosa to contract, increasing the rigidity of the erection. The pudendal nerve also conveys sensations of sexual pleasure and orgasm from the penis back up to the brain.

In a reflexogenic erection, however, the process is somewhat different. Direct sexual stimulation sends neural impulses up through the penile dorsal nerve to the spinal erectile center; from there, stimulation travels back down to the penis via the parasympathetic and cavernous nerves, without being modulated by the brain.

Neurobiochemical processes at the molecular level underlie the physiology of erection. During sexual arousal, the previously described parasympathetic nerve stimulation to the penile tissue causes the release of neurotransmitters and other chemicals from the nerve terminals and the vascular endothelium (the lining of the arteries and sinuses) in the penis. These chemicals cause smooth muscle relaxation and dilation of the cavernous blood vessels and their tributaries, the helicine arteries, which supply blood to the vascular sinuses in the corpora cavernosa. The synchronized widening of these vessels and sinuses produces tumescence by increasing blood flow to the penis.

Within the corpora, the endings of nonadrenergic/noncholinergic nerves secrete the neurotransmitters acetylcholine and nitric oxide (NO). NO may also be released from the vascular endothelium. NO is produced in the body by the action of the enzyme nitric oxide synthase on the substance L-arginine in the presence of adequate dihydrotestosterone. NO is the chemical considered to be principally responsible for the vascular dilation in erection. It may also be involved in storing and propagating neural impulses in the spinal cord and the pelvic nerves.

It seems that the oxygen content of the penile tissues and the level of testosterone in the bloodstream also significantly affect the secretion of NO. Therefore, any obstruction of the penile vessels that precludes normal delivery of oxygenated blood to the penile tissue may impair the secretion of NO and lead to ED.

NO penetrates the smooth muscle cells in the walls of the penile arteries and sinuses, where it stimulates the enzyme guanylate cyclase to convert the naturally occurring compound guanosine triphosphate into another substance required for erection, cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). A potent smooth muscle relaxant and vasodilator, cGMP relaxes the vessels by lowering the amount of calcium inside their muscle cells to reduce the muscle tone.

With the resulting dilation of the penile vessels, blood flows rapidly into the penis at high volume and progressively increasing pressure. This pressure may exceed the systolic pressure (blood pressure during heart contractions) in the rest of the body’s peripheral arteries. The cavernous tissues become engorged with blood, which stays in the penis because the penile veins are compressed, and with the accompanying contraction of the penile muscles, erection is achieved and maintained (see following section).

Additional substances, including vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), calcitonin gene-related peptide, adenosine, cyclic adenosine monophosphate, adenosine triphosphate, and prostaglandin El, have been reported to be involved in the erectile process as well. Others may yet be identified; for example, it was recently discovered that activation of calcium-sensitizing pathways contributes to penile flaccidity, whereas their deactivation contributes to erection.

If this were the case, the penis would be in a constant state of erection. This could be quite painful, not to mention embarrassing and potentially dangerous.

Prior to arousal, when the penis is totally flaccid and its arteries and sinuses are contracted, penile blood flow is low, amounting to about 1–2 milliliters per minute, but when sexual stimulation and excitement produce penile vasodilation, penile blood flow increases to about 90 milliliters per minute.

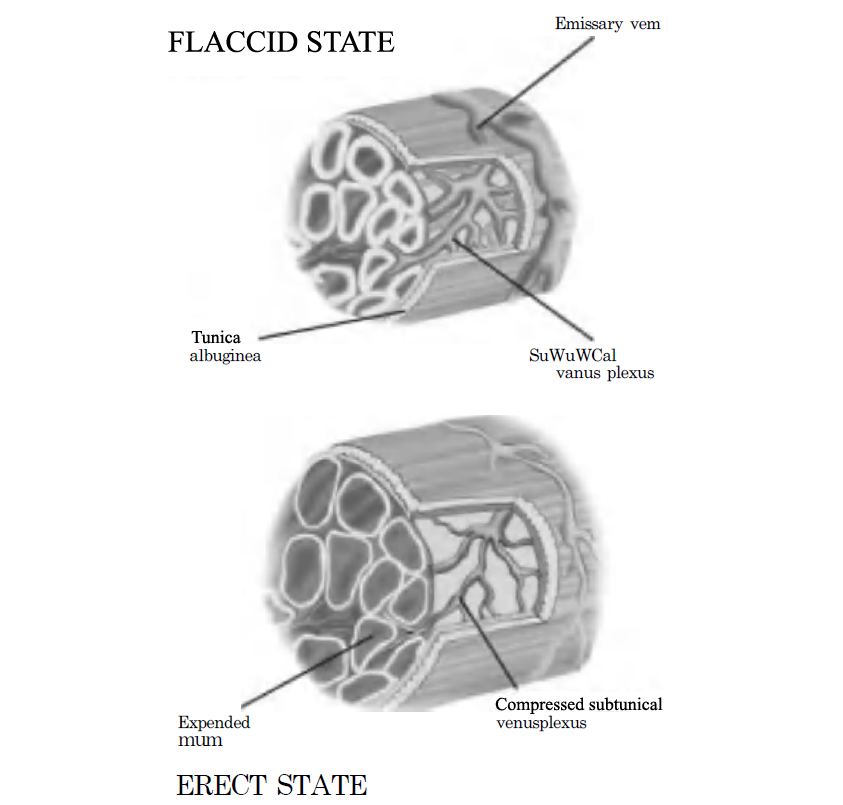

This increased inflow to the corpora swells the penis, which becomes tumescent: longer and thicker but not yet hard. Then, as more blood flows into the penis and the corpora (mainly, the cavernosa) become engorged, the dilated penile sinuses crowd and compress the veins of the penis against the tunica albuginea. This compression dramatically reduces the penile venous outflow, trapping blood within the penis.

With more blood coming in than going out, pressure in the penis builds, pushing in all directions—much like an inflating balloon—and as a result of this pressure the congested penis straightens, elongates, expands, and becomes firmly erect. Once the penis is full to capacity, blood flow both in and out of the corpora decreases to a minimum and then stops completely after the ischiocavernous muscles contract, maintaining a rigid erection (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1: Mechanism of the Erectile Process (Courtesy of Alexander Balmaceda)

In principle, yes, with a major qualification: his arteries must be healthy, and there must be no abnormal leakage of blood from the penis through the veins. As detailed previously, erection is produced not only by increased penile arterial blood flow, but also by decreased penile venous outflow. (If this outflow decreases too much for too long, an overly prolonged erection, or priapism, may pose a serious problem.)

The length of time a man is able to maintain an erection is an important facet of his normal sexual functioning. Most young men can maintain a firm erection for at least 5-15 minutes, and some individuals for more than half an hour. On average, after penetration, most men can sustain their erection for about 8–10 minutes before ejaculation. The number of orgasms experienced successively during intercourse also varies from man to man. Most are satisfied with one orgasm per sexual encounter, but others need several for total satisfaction. Medically speaking, and in the absence of any sexual dysfunction, all of these men are so-called normal.

After orgasm and ejaculation, or when erotic physical and psychological stimulation ceases, the penile arteries and sinuses narrow to their normal diameter, the veins are decompressed, and the unimpeded outflow of blood from the penis leads to the loss of the erection and the return of flaccidity.

As detailed previously, dilation of the penile arteries and vascular sinuses is principally controlled by the nitrergic system, based on the secretion of neurotransmitters and vasodilators (NO, acetylcholine, cGMP, and such) from the parasympathetic nervous system and the vessels’ lining. By contrast, constriction of the penile arteries and sinuses is principally controlled by the vipergenic system, which relies on VIP, on secretion of the vasoconstrictive hormones adrenaline and noradrenaline from the sympathetic nervous system, and on beta-2 adrenergic receptors to keep the penile vessels and sinuses partially closed.

Other substances called endothelins, secreted by the vessels’ lining, may also contribute to constriction of the penile vessels. Chemicals such as prostaglandin F2a, prostanoids, and angiotensin II are involved as well. These vasoconstrictive substances restore the normal resistance to increased blood flow in the penile arteries and sinuses, preventing the occurrence of a subsequent erection for the duration of the refractory period. As previously noted, this period lasts from a few minutes to several hours, according to the man’s age and other factors.

Activity of VIP, endothelins, and norepinephrine, in fact, may underlie psychogenic ED, as they contract the penile arteries and sinuses in response to stress, anxiety, and other psychological or emotional factors.

A persistent, possibly painful erection not associated with ongoing sexual desire or pleasure is called priapism. It can last for more than four hours and may cause penile damage if left untreated.

For appropriate treatment, it is important to determine whether the condition is low-flow or high-flow priapism. Of the two, the low-flow or ischemic type, due to entrapment of blood in the corpora cavernosa with reduced outflow of blood through the veins, is more common. Intracorporeal injection of vasodilators is the most frequent cause of low-flow priapism. Other causes follow:

In some cases, even a thorough evaluation cannot identify the priapism’s etiology.

When it is the low-flow type, Doppler ultrasonography shows no blood flow inside the penile vasculature, and analysis of a sample of the dark blood drawn from the corpora reveals low oxygen content with acidosis (accumulation of acid). Untreated, this emergency condition can result in poor oxygenation of the penile tissue, cell death, and severe scarring.

Management of low-flow priapism depends on its duration, etiology (if known), and symptom severity. The initial measures—which are usually not very successful—include ice packs, sedatives, analgesics (for pain), intranasal oxygen, and oral terbutaline (a vasoconstrictor). The next steps, if needed, are the aspiration of blood from the corpora; intracorporeal injection of vasoconstrictors such as phenylephrine, epinephrine, or aramine; and/or manual compression of the penis for several minutes, which may yield good results. If these fail, or if the priapism recurs after a period of detumescence, one of several surgical techniques is used to shunt blood from the affected corpus cavernosum to the corpus spongiosum (which is not involved in the pathology) or to the saphenous vein in the upper leg.

High-flow priapism usually results from blunt trauma to the penis or perineum. In these cases, the abnormal erection is typically softer and non-painful; the aspirated blood is bright red, well oxygenated, and non-acidotic; and Doppler ultrasonography shows adequate penile blood flow. High-flow priapism does not require emergency measures and may subside spontaneously without treatment or simply with manual compression of the penis. But if it persists, embolization (occlusion by scarring solutions or coils) or surgical ligation (tying off) of the bleeding penile vessel can be performed, with excellent results.

Stuttering priapism is a term for low-flow priapism’s frequent recurrence after initially successful therapy. Several oral medications, such as Bicalutamide, Baclofen, Ketokonazole, Flutamide, gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (which mimic the action of GnRH), and digoxin, have been effective in preventing stuttering priapism. Recently, two of the phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (Viagra – sildenafil, and Cialis – tadalafil) have also been used successfully for this purpose. In rare cases that don’t respond to conservative nonsurgical measures, the patient may be instructed to inject his penis with a vasoconstricting substance whenever a prolonged involuntary erection occurs, or he may require a surgical shunt, as described previously.

If ED develops secondary to priapism or surgery for priapism, a penile prosthesis can be inserted.